A short story

By Martin Davies

Sometime in early 1952, my grandfather, Francis “Frank” Cowen, boarded a train to Wonthaggi.

Wonthaggi was then the terminus of a railway line that ran all the way to Nyora where it joined the now partially closed South Gippsland rail line.

He was alone. He carried nothing more than an overnight bag and a few light timber beams.

Frank was a WWI veteran who fought at the Somme. He probably carried undiagnosed trauma from this experience, but if he did, he seldom displayed it. Occasionally he would be quick to anger, and he drank too much. When he had a drink, he was a man to be avoided. But otherwise he was as good a father as a father can be.

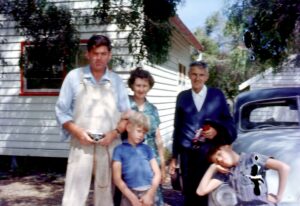

Frank was about 6 foot tall, and had dark strong hair, green eyes and a slight build. He was called “Lofty” in the army. He enlisted on 9th July 1915, joined the 49th infantry battalion, and embarked Australia on 11th October on the Nestor.

But all that was in the past. His army days were behind him.

Frank arrived at Wonthaggi station and alighted from the train. The timber beams that he carried had been salvaged from the National Mutual Building in Melbourne where he had worked.

Now Frank was retired and finally he had time to enjoy life.

He put the timber down on the pavement and rested for a while.

It was hot. He thought about walking the short distance to the Whalebone Hotel across the street. He could get a cold beer there. But he decided against it and put out this thumb instead.

He managed to hitch a ride to Inverloch which was just over eight miles down sandy, unsealed road. Frank got off at the corner of Toorak Road and Bass Street (now Evergreen Street), thanked whoever it was that gave him the lift, and walked the short distance to his destination.

It was the beginning of a long journey—for his family, and mine.

Frank had just purchased land from the state government. The land was located on what was then Beach Road West. Much later, the road would be renamed Beacon Court owing to a perceived confusion for emergency services between two streets called Beach Avenue. But this occurred much later. For decades, Beach Avenue West was a pilgrimage for Frank. For Frank was the first private owner of what was previously Crown land.

He was a pioneer, of sorts.

The land was close to Anderson’s inlet, one back from the Esplanade. It was less than a minute’s walk from the rickety old Ayr Creek bridge—now long since replaced. The land was close enough to the inlet to hear the pounding surf, and yet settled amongst some mature peppermint gums in a large bush garden.

The block next door was virgin scrub too. It remains so to this day. It was the site of an original beacon that once provided safe passage for boats entering the inlet. It then became a precious thoroughfare for wildlife moving from the inland grazing areas to the scrub along the Inverloch foreshore. Koalas. Echidnas. And lizards of various kinds.

On Frank’s block koalas and birdlife were plentiful. This is still the case. When Frank visited Inverloch, it was like he lived in his own sanctuary; surrounded by bush, and a stone’s throw from the isolated, moody beach at his doorstep.

There was no house on the block, and so Frank initially slept in a small tent. He used a crook in a tree to place a basin and used this for his daily ablutions. Over many months of travelling by train with building materials he accumulated sufficient timber to erect a small shed.

During the day he used a long-handled scythe to cut the overgrown bracken fern on the site. It was a large block, and the site was measured in links: 336.71 x 66.41.

The days were either spent building, or slashing bracken with his scythe.

His only company—the birds and animals.

And the crashing surf.

Frank always travelled to Inverloch alone.

Over time, the shed became Frank’s sleeping quarters, and—inevitably—bigger things were planned.

One of Frank’s sons, Leslie (“Mick”) Cowen, became a builder. This was convenient, because Frank had outgrown the shed, and now needed a house. By this time, Frank had purchased his first car. He was well into his 60s by then. Trips to Inverloch with building materials became less arduous, and with Mick’s help over many years, a house was eventually erected.

With a house to sleep in, Frank could finally bring his Irish-born wife.

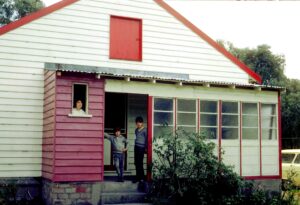

It was a very simple house: A square box on stumps essentially. 25 feet x 24 feet.

The house had a large gable roof with an external access door high up the wall accessible only by a tall ladder. Frank had made the ladder himself out of hardwood. Inside the roof cavity there was sufficient space inside for a grown man to stand. But the space was never used for a room. Instead, it housed a gravity-fed hot water system, and used as a timber storage area.

The interior design of the house was poor by modern standards, but it was adequate for a holiday shack. It had two ample-sized bedrooms with small timber sash windows. There was a decent-sized kitchen and separate bathroom, and a laundry reached from outside the house via a separate door. Inside the small house, there was a short corridor. This was used for nothing more than foot traffic. It used up vital space in the small house.

Outside the house a simple, home-made box with ceramic fuses provided the source of electrical power. Every so often, there was an electricity overload, and the power went off. This required the fuse wire to be re-attached by hand.

The house wiring was almost certainly done by Frank. He was not an electrician, and his electrical work was non-compliant. It’s a wonder the house didn’t burn down. But in those days people did things as best they could. They didn’t have the rules and regulations to follow that we have today.

It was an era of “making-do”.

The original shed where Frank slept for many years stood alongside the south-west corner of the house. Between the shed and house there was a lean-to set on a rough, uneven home-made concrete pad.

The lean-to was little more than salvaged office dividers from the National Mutual Building joined together with off-cuts of timber and covered with bits of second-hand corrugated iron. Chicken wire was shoved into the gaps between the roof and the walls to try to keep insects out.

It was nothing special—but it kept the rain off the front door. Birds would nest inside the lean-to as it was dry. It formed the intermediate zone between the house, and the wildlife haven that surrounded it.

Time passed.

Frank and his wife Geraldine visited Inverloch as often as they could. They used to walk down the beach a lot. There was little else to do. They’d walked along the windy esplanade road. They’d also pass through the thickets of dense tee-tree that lined the foreshore to stroll along the beach.

Inverloch was not the holiday town it is today. There were very few buildings. There was the pub, the Inverloch guesthouse, a butcher, a general store and that was about it.

Inevitably, over time, the town developed. A pop-up cinema appeared during holiday periods. The cinema was nothing special. It was a timber-framed building close to where the Community Centre is now. They used to show reel-to-reel movies occasionally. The newsreel was a highlight. Patrons sat on uncomfortable wooden chairs on a timber floor. The cinema remained there until the 1970s when kids would ‘roll jaffas down the aisle’. Then the pop-up cinema disappeared. As they were poor, it is unknown if Frank and his wife ever visited the movie house.

Sometimes, when they visited the beach Frank fished. He had a long bamboo fishing line with a large spool.

When he fished, his wife, Geraldine, sat under the large trees near the foreshore to shelter her pale Irish skin from the hot Australian sun.

Frank and Geraldine had met in England when he was posted to Europe during WWI.

They met towards the end of the war when Frank was on leave. They decided to marry, but the troops were still not disbanded and were sent all over England until a troopship was available to take them home. Therefore Frank and Geraldine did not marry until he and Geraldine arrived in Australia in 1921. The ceremony was at the Free Church, South Yarra, on 14th February.

They returned to Australia together with a baby later named Douglas. The baby was not Frank’s—but he raised the boy as his own.

One of Frank’s first jobs was with Luna Park in Sydney. It was close to where his mother and he were living. Later, he became a labourer with the Victorian Railways, and gradually worked up to be a station master. In those days the station master was decked out like a general, with a gold trimmed peak cap, dark uniform trimmed with gold buttons, a white shirt with very stiff collar and a black crocheted tie. He looked very smart.

When he returned from the war, Frank was posted to Piangel. This was a branch line of the Deniliquin line north of Bendigo running north-west past Swan Hill, and parallel to the Victorian and NSW border. Piangel was the terminus of the line. Even now, this is a dot on the map in the featureless Australian bush. One wonders how Geraldine, an Irish girl, coped coming from emerald-green Ireland to the strong light and windswept, sun-baked horizons of Piangel.

But she did.

Frank and Geraldine had nine children: Doug, Sydney, Arthur, Mick, Pearl, Alva, Fredrick, Frances, Daphne. There were two sets of twins: Doug and Sydney, and Frances and Fred. Sydney died in infancy. With the exception of Arthur, the other kids lived long and fulfilling lives. Sadly, Arthur Cowen died of pneumonia at the age of 13. He acquired this after lying on hot railway tracks to dry out after swimming in the dams. Arthur was a frail boy, but very musical. He won one of only three medals awarded in Australia for his precocious violin playing.

He never lived long enough to receive it. His many certificates remain with the family; a testimonial tribute to a talent taken before his time.

Frank and Geraldine had done their duty as parents. But now they were retired, and they had a holiday shack at Inverloch.

They named the little house ‘Anembo’, apparently an aboriginal word for ‘Resting place’.

Anembo.

Resting place.

Frank tinkered in the garage. He eventually replaced the scythe with a petrol mower and used it keep the bracken fern at bay. Over time, a lawn of sorts became established. He burnt off the bracken and wind-drift in an incinerator. They sat together at dinner with nothing more than the sounds of the birdlife to accompany them. They talked. Sometimes they played cards. There was no such thing as TV.

The slept in the quiet of the night; they breathed the clean, crisp coastal air.

Anembo.

Resting place.

It was a place where time moved slower. The days passed, and they enjoyed simple pleasures. They sat under trees reading books. They worked the garden. They walked to the beach and to the few small shops in town. They looked with admiration at the more salubrious Inverloch guesthouse which was positioned on a hill in the middle of town. More well-to-do people would stay there. They could see the fancy cars in the parking area. They watched the guests play tennis.

However, Frank and Geraldine were happy with their lot. They had a home away from home. It was a small house, but it was adequate. It sat among the large peppermint gums. It was close to the beach. It was a place where the wildlife lived together with humans with a degree of equanimity.

The other children visited with their families. Mick and his brother Fred helped their father by making refinements to the house. A water tank was installed. They used it for their water supply even though it was full of “wrigglers”.

Over time, Anembo became a home away from home for the entire Cowen clan.

Geraldine passed away in 1962 from heart disease.

Frank survived until 1968 when he passed away from cancer. Having experienced the 1920s depression, at one time Frank sold pencils and small items on street corners to make a living. A hard man who had been to war, he knew the meaning of deprivation and suffering. Nonetheless, he made some shrewd investments. By the time he died he managed to leave a block of land to all his children—with the exception of Mick, the builder, who had already built himself a house.

This gave his children a start in life.

He bequeathed Anembo to his second eldest daughter, Alva. Of all the children, she and her husband Bill had shown most interest in the house and land. Bill was also handy around the house and helped Frank fix things. Frank was an impatient man and not very technically-minded; the sort of man who would throw things away readily even if they could be easily fixed.

Bill was a quiet, patient man who could be trusted to do things that needed doing.

Alva and Bill became the new owners of Anembo. As in the normal way of things, they had children of their own, a son and a daughter. The little house became a home away from home for a new family. Once a place of rest for Frank and Geraldine, it became a retreat for a new family.

Anembo.

Resting place.

Alva and Bill had regular visitors. The extended Cowen clan, their partners and children, all stayed at the house on occasions. Christmas holidays were a chaotic affair with tents in the backyard, cricket games being played on the lawn, lazy days on the beach, long walks to Eagles’ Nest and—most excitingly for the kids—trips to the old Inverloch carnival and the ice cream parlour.

By then it was the 1970s. The Inverloch fair was the most exciting thing in town. This was located above The Glade where the boat hire place is now. Throughout the year the carnival was a moribund affair: a series of sad-looking, destitute caravans, with equally destitute owners.

During the Christmas holidays, however, it came alive. A very obese man lived all through the year in a caravan behind all the amusements. His role was to take care of the equipment during the year. He wore blue overalls and seemed to have only one tooth. During the day he employed some of the young boys to clean and wax the slides. Bill and Alva’s son Martin, and his cousin Glenn, were recipients of the one-toothed man’s largesse. They cleaned and waxed the slides. They sometimes bounced on the trampolines for free.

At night the carnival was a blaze of colour and sound—an irresistible magnet for the children of holiday-makers, and the locals. It had rocking horses that spun around a central motorised pole, trampolines, and a laughing clown game. This rather terrifying thing required ping-pong balls to be placed in the mouth of clowns as they jerked their macabrely-painted heads from side to side. The balls traversed segmented tracks illuminating scores on a screen above. A certain number of points would win a prize. There was also a game that illuminated playing cards on a screen. There must have been other attractions, but time has dimmed the memories.

Further along the street from the carnival was a pin-ball place. It was called ‘Flea-bags’ by some locals. It had one or two pin-ball machines and a pool table. Around the room there were some old furniture and sofas. That was it. Local boys used to come and smoke cigarettes at Flea-bags. To the side of the play room was another room. In it sat some old people who perpetually watched television.

Flea-bags always seemed to emanate dust. Hence the name I suppose.

At Anembo life went on as usual.

During the day, the kids went to the beach. They loved long walks through the dense tee-tree scrub. They had names for some of the beach trails that traversed the dunes from the Esplanade to the foreshore. One of the best was “The Big Dipper”. It seemed to go on endlessly. Sometimes the kids rode their bikes up and down the dunes, but usually they ran wildly from one end to the other shrieking with laughter as they went. They returned to the house tired, hungry and wet after being out all day at the beach. They were raw with sunburn and covered in sand.

There were plenty of things to do at the house. They built a tree-hut. The kids also pretended to be shopkeepers by selling items through the window of the old shed. Inside the shed there was an old wind-handle gramophone with a number of 78rpm records from the 1930s, 40s and 50s—the property of Frank Cowen. The records were shellac and always covered in dust and cobwebs. One of the records was ‘Auctioneer’ by Leroy van Dyke.

There was a boy in Arkansas

Who wouldn’t listen to his ma

When she told him he should go to school.

He’d sneak away in the afternoon,

Take a little walk then pretty soon,

You’d find him at the local auction barn.

He’d stand and listen carefully.

Then pretty soon he began to see

How the auctioneer could talk so rapidly. ….

The kids memorized the auctioneer song spiel. They gave concert ‘performances’ for the adults, emerging from the shed in fancy dress. The adults dutifully purchased ‘tickets’ and took their seats in the ‘concert hall’. They found the performances very funny.

There were regular BBQs in the yard on an old steel tray positioned above a fireplace. In the evening the adults played cards, and there were rosters for cooking duties and dishwashing. The roster wasn’t popular, of course, but it had to be done. Sometimes Christmas day was spent at Anembo and the Christmas tree was set up on the porch under the lean-to amidst the bird droppings and lizards.

It was all good fun. Many good memories were made.

Life was simple.

New Years’ Eve was fun. Back from the esplanade, the streets were always dead quiet. Close to midnight the kids would run down the back streets banging pots and pans to rouse others.

The eerie quiet of the dark Inverloch streets swallowed their efforts.

In-between family trips, Bill and Alva rented the old house to help cover costs.

One permanent tenant was a Miss G., a home economics teacher at a local school. Ironically, she was the dirtiest tenant they ever had—leaving piles of rubbish such as old magazines and newspapers for the owners to get rid of when she finally left. Another tenant, Mr B., a painter, accidently burnt a hole in a quilt and compensated for this by painting the masonite walls of the old kitchen with a fresh coat of enamel olive-green paint.

It was the thought that counted.

Other visitors to Inverloch slept on the beach during the summer. In the 1970s the foreshore was a city of tents. From beyond the surf beach all the way to town there was a sea of canvas. The tents were close together. Bonfires were lit at night. People became very drunk. Loud music filled the air.

Human activity was interspersed with the ceaseless sound of the crashing surf.

Time passed.

Bill and Alva greatly improved garden during their stay over many decades. Camellias were planted at the rear of the yard. When they matured they provided a great floral display in winter and spring. This burst of colour contrasted with the muted greens of the gum trees, banksias, pittosporum, and the darker-green of the bracken fern.

The lawn slowly improved too. Bill planted runners of buffalo grass that eventually took over from the ubiquitous bracken fern—the fern that Frank laboriously cut with his scythe, and his mower, many years before. The house was painted regularly. Gutters were cleaned. Things were fixed as they needed to be.

But the little house remained much the same. It served its purpose as a holiday shack. The gravity-fed hot water system from another era served the family well as the twentieth century rolled into the twenty-first. It was turned on when one arrived at the property and the next day one would have hot water.

The lean-to on the back of the house harboured birdlife and the occasional lizard. The moods of the garden waxed and waned; seasons came and went. The thunderous surf of the inlet became a background to the comings and goings in the house.

When unattended, the house sat alone but proud amidst the noises of the bush.

Bill passed away tragically in 2003. He acquired a brain disease and took his own life on his own terms. It was a great loss to his wife and children. But life at Anembo went on. His son, Martin, stepped into his new role as custodian.

It’s the natural way of things.

One day in 2004 everything changed. Once too often the old heater tripped the electrical wiring and the power went out. It was time to do something. They set out to renovate the old house, a house now held now for over five decades by the one family.

Martin had few practical skills. He could demolish things though.

That was one way to start.

Martin had a friend from his university days in Adelaide. Dale was as dependable as they come. He was a biology research assistant who specialised in lizards. He also had a side-interest in car number plates and his house walls were lined with them. Dale visited Melbourne every Christmas period to visit his father and sisters. He was adopted and never really knew his birth mother and father.

Dale was asked to help.

The first thing to go was the lean-to. This was unbolted from the house and entire frame was pushed over. It fell to the ground in an explosion of glass and timber bits. Frank’s rough-hewn concrete porch was demolished with a jack hammer. The masonite was then stripped from the walls of the bedrooms, and the canite from the ceiling. The bathroom utilities and hand-made kitchen were stripped out. Everything was carted to the Inverloch tip.

By removing the wall cladding the house was a mere shell.

For a while it was uncertain what could be done.

Eventually Martin made the acquaintance of a local handyman, Terry. Having the appearance of an old sea captain—with a thick beard and a bung eye—Terry saw things that could be done to the old house.

‘It’s built well’, he said, as he surveyed the job.

Terry first built a deck at the back of the house where the lean-to once stood. Martin helped out as best he could. When completed, it measured 4 x 7 metres. Over time, and over many months, Terry remodelled the interior of the house too. The old kitchen became a bedroom. The short passage way became part of a new lounge room looking out to the expansive rear yard. Externally the house remained as it was. Internally, it took on a commodious new life.

Hundreds of Inverloch holiday-makers have since made use of Frank’s house—the small house among the peppermint gums.

The house built by the man who carried pieces of timber to Wonthaggi by train, and then hitch-hiked the remaining distance.

The man who scythed the land by hand.

The man who slept in a tent until the job was done.

What is to become of Anembo—the resting place?

In time, it will be passed on to a new generation, just as was done twice before.

For it doesn’t belong to anyone.

It belongs to the land on which it sits.

It belongs to the trees. The camellias. The bracken fern. It belongs to the lizards and birds. The koalas and echidnas.

And the sound of the crashing surf.